Out from Scott's Shadow: Zelda Fitzgerald's quest for creative autonomy

A toxic, competitive relationship that did neither of them any good

Hello, on this hot and humid Wednesday. I’m just back home (in the Hudson Valley region of NY State) after two weeks of cat-sitting, working from said cat-sit (deadline for Women Writing Dangerously continues to loom), and discovering many amazing things in Copenhagen.

July is my least favorite month (see above: heat and humidity), giving me the perfect reason to stay inside of libraries and work on my book deadline. As I’ve mentioned, I’m documenting the process of how a messy manuscript (tentatively titled Women Writing Dangerously) will become a beautiful visual book (out in September 2026) in my Notes here on Substack. Here’s one from today about Peyton Place by Grace Metalious.

I’m still pretty tired and jet-lagged so I’m turning to one of Literary Ladies Guide’s most intrepid contributors, Elodie Barnes, for this long and lovely post about Zelda Fitzgerald. Poor Zelda, ever in the shadow of her far more famous husband, wanted so much to achieve a creative life of her own. It all ended so sadly for both of them. F. Scott Fitzgerald’s literary legacy was cemented after his death; Zelda’s achievements began to slowly emerge some dozen years ago.

And now, Elodie takes it from here …

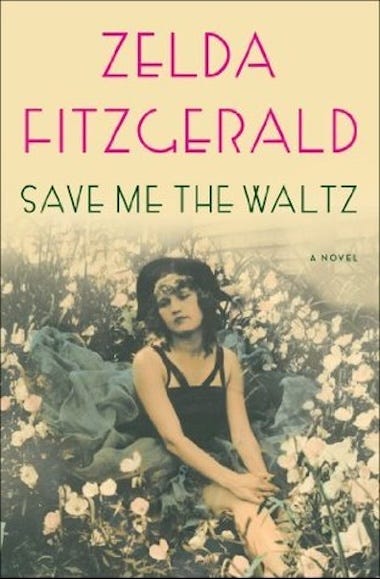

Zelda Fitzgerald (1900 – 1948) may be best remembered as the wife of writer F. Scott Fitzgerald, but she was a talented painter, dancer, and writer. Here’s a look at the creative life of Zelda, including Save Me the Waltz and other writings, along with her contentious, competitive relationship with her husband.

Struggling first against the excesses of her own Roaring Twenties lifestyle (she was sometimes referred to as “the first flapper”) and then battling mental illness, Zelda never achieved critical success, nor did she have the chance to fully develop her skills. According to the couple’s daughter Frances (Scottie) Fitzgerald:

“It was my mother’s misfortune to have been born with the ability to write, to dance, and to paint, and then never to have acquired the discipline to make her talent work for, rather than against, her.”

It has only been relatively recently that her creative achievements, and her writing, in particular, are starting to be revisited and re-examined.

The search for a creative outlet

Throughout the 1920s, Zelda and Scott were one of the most famous Jazz Age couples of the era. They had lived the high life in New York and had then shifted across the Atlantic, following the tide of so many other Americans seeking the relative artistic and sensual freedom that France offered.

Soon they were riding the rollercoaster of parties, alcohol, infidelity, and excess in Paris and on the Riviera. Scott was enjoying his success, busy writing the short stories that paid some of the bills and working on the next novel, but Zelda was becoming increasingly frustrated at her own lack of a creative outlet.

As a child and teenager, Zelda had been an accomplished dancer. She had also written a few short “guest celebrity” pieces early in her marriage, including a review of Scott’s novel The Beautiful and the Damned, but as a woman and wife of a famous author, she was not expected to have the talent of her own. However, Zelda found that she had no desire to be simply a wife and mother and muse to her husband.

In 1927, already in her mid-twenties, Zelda started taking ballet lessons again. She studied with notable teachers including Lubov Egorova in Paris, and it soon became an obsession that preoccupied her for up to eight hours a day.

These lessons were reluctantly paid for by Scott, an arrangement which Zelda also disliked intensely. To support herself and to be able to pay for her own lessons, she began to write. Articles and short stories including Our Movie Queen, Miss Ella, and A Couple of Nuts were published in Harper’s Weekly, The Smart Set, and The Saturday Evening Post.

Most of the stories appeared under her husband’s name. The F. Scott Fitzgerald byline fetched a far higher price and made it easier to get pieces accepted, but it also meant that Zelda struggled to establish any kind of writing the identity of her own.

Zelda also faced challenges in the ballet studio. She was too old to achieve her dream of becoming a prima ballerina. Yet in the autumn of 1929, she was offered a salaried position with the San Carlo Opera Ballet Company in Naples, dancing a solo role in Aida with more solos to follow during the season, but had to decline the offer, as she was not mentally capable of fulfilling the demanding contract.

Declining health and mental illness

Within months, she was hospitalized with hallucinations, anxiety, depression, and exhaustion. She discharged herself against her doctor’s advice, desperate to return to the ballet studio, but within weeks she had relapsed.

This time she was sent to a hospital in Switzerland, where the doctors recommended psychological treatment. After seeing a highly sought-after psychiatrist, Dr. Oscar Forel, she was diagnosed with schizophrenia.

She arrived at the clinic in Switzerland in June 1930 and stayed for over a year. The rest of her life would be spent in and out of hospitals and sanatoriums in both Europe and the U.S.

Save Me the Waltz and tensions with Scott

In early 1932, she was a patient at the Phipps Clinic outside Baltimore in Maryland. It was here that she wrote the first draft of her only novel, Save Me The Waltz, in just two months. It tells the story of Alabama Beggs and her painter husband David, whose artistic success and flamboyant lifestyle lift them from their Southern roots into a whirlwind of New York celebrity. It’s a clear roman à clef based on her own life and, to a lesser extent, that of her husband.

It was far from her first foray into writing fiction, but it was the first time she had written anything and sent it to a publisher without showing it to her husband beforehand. She chose Max Perkins, her husband’s editor, writing to him,

“Scott completely being absorbed in his own [novel] has not seen it, so I am completely in the dark as to its possible merits but naturally terribly anxious that you should like it.”

Zelda wanted desperately to be taken seriously as a writer, and for the first time wanted her work to be evaluated on its own merits, without her husband’s intervention, opinion, or the use of his name.

When Scott saw the novel soon after, he was furious. He accused her of plagiarizing several ideas from his current novel-in-progress, Tender Is the Night — “literally one whole section of her novel is an imitation of it, of its rhythm, materials…” — and of exposing too much of his private life.

He was also angry that she had named one of her main characters Amory Blaine, a name that her husband had also used in This Side of Paradise. Scott fumed:

“This mixture of fact and fiction is calculated to ruin us both … my God, my books made her a legend and her single intention in this somewhat thin portrait is to make me a nonentity.”

Zelda wrote to Scott to try and explain why she had not sent him the manuscript first:

“Purposely I didn’t — knowing that you were working on your own and honestly feeling that I had no right to interrupt you to ask for a serious opinion. Also, I know that Max will not want it and I prefer to do the corrections after having his opinion … I did not want a scathing criticism such as you to have mercilessly — if for my own good given my last stories, poor things. I have had enough discouragement, generally, and could scream with that sense of inertia that hovers over my life and everything I do.”

Fantasy versus reality

It wasn’t the first time that the lines between fact and fiction had become blurred. Scott, too, often conflated fantasy and reality in his novels: he once said to Malcolm Crowley, “Sometimes I don’t know whether Zelda isn’t a character that I created myself.”

In her 1922 review of her husband’s novel The Beautiful and Damned, Zelda had written:

“It seems to me that on one page I recognized a portion of an old diary of mine which mysteriously disappeared shortly after my marriage, and also scraps of letters which, though considerably edited sound to me vaguely familiar. In fact, Mr. Fitzgerald — I believe that is how he spells his name — seems to believe that plagiarism begins at home.”

Indeed, Scott used lines from Zelda’s letters and diaries throughout his writing career, most notably in This Side of Paradise, The Beautiful and Damned, The Great Gatsby, and Tender Is the Night.

Scott, on the other hand, didn’t appreciate Zelda doing the same thing. While his side of the correspondence has been lost, he must have sent Zelda a curt reply to her explanatory letter, because, in her next letter to him, Zelda wrote:

“I glad[ly] submit to anything you want about the book or anything else … However, I would like you to thoroughly understand that my revision will be made on an aesthetic basis: that the other material which I will select is nevertheless legitimate stuff that has cost me a pretty emotional penny to amass and which I intend to use when I can get the tranquility of spirit necessary to write the story of myself versus myself.”

After Save Me the Waltz: subsequent writings

Save Me the Waltz was published in 1932 in a print run of likely no more than 3,000 copies. Only around 1,200 sold, and the novel went out of print after this first run.

Its publication did not ease any of the tensions between the Fitzgeralds. Zelda wanted to continue to write, while Scott told her she was “a third-rate writer and a third-rate ballet dancer … I am a professional writer, with a huge following. I am the highest-paid short story writer in the world.”

By 1934, Zelda and Scott had separated (though they never divorced). In her last years, Zelda lived at Highland Hospital in Asheville, North Carolina, where, as an inpatient, she pursued her creative ventures, including painting. She continued to study dance and to write. Gallery exhibitions didn’t garner her much attention; you can see some of Zelda’s little-known artwork here.

Zelda started another novel, Caesar’s Things, and worked on it intermittently for the rest of her life. It never came to anything. She also turned to scriptwriting and attempted to produce a play called Scandalabra, described as a fantasy farce in a prologue and three acts.

On March 10th, 1948, a fire broke out at Highland Hospital while Zelda was in residential treatment. She died in the fire along with eight other female patients. Zelda is buried next to Scott in Old St. Mary's Catholic Church Cemetary in Rockville, Maryland.

Zelda’s Legacy

Save Me the Waltz was republished by Southern Illinois Press in 1967 (it required some 550 spelling and grammar corrections), and then again by the University of Alabama in 1991 in The Collected Writings of Zelda Fitzgerald. More recently, it has been reissued by Handheld Press.

Some of her other writings have recently been unearthed, for outlets like Harper’s Bazaar, New York Tribune, and even quite a few for, of all things, College Humor. Here’s more about the little-known writings of Zelda Fitzgerald.

Interest in Zelda’s writing and life surged after the 2013 film adaptation of The Great Gatsby. In addition, several novels have been based on her life. One of them, Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald by Therese Anne Fowler, was adapted into an Amazon Prime original series, Z: The Beginning of Everything.

. . . . . . . . .

Contributed by Elodie Barnes. Elodie is a writer and editor with a serious case of wanderlust. Her short fiction has been widely published online, and is included in the Best Small Fictions 2022 Anthology published by Sonder Press. She is Books & Creative Writing Editor at Lucy Writers Platform, she is also co-facilitating What the Water Gave Us, an Arts Council England-funded anthology of emerging women writers from migrant backgrounds. She is currently working on a collection of short stories, and when not writing can usually be found planning the next trip abroad, or daydreaming her way back to 1920s Paris.

Further reading:

Save Me the Waltz by Zelda Fitzgerald, Handheld Press, 2018

The Collected Writings of Zelda Fitzgerald, ed. Matthew J. Bruccoli,

University of Alabama Press, 1997 (3rd ed)Zelda Fitzgerald: Her Voice in Paradise by Sally Cline, John Murray, 2003

Dear Scott, Dearest Zelda: The Love Letters of F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald,

ed. by Jackson R. Bryer and Cathy W. Barks, Bloomsbury, 2003Z: A Novel of Zelda Fitzgerald by Therese Anne Fowler, Two Roads Press, 2013

Amazing analysis, and thank you also for the links because I had never seen her paintings, and they are pretty good!